Mind as a Figment of Yours, and, Reason to Pragmatism

Mon, 14 October 2024Find this as a PDF or on Substack.

Is the mind physical? Is it mental? Is it both? My answer is that it is only physical, it is only mental, it is both physical and mental, and neither physical nor mental, all at the same time. Of course, it is a bit more nuanced than that. Inquiring into minds and their nature is more than understanding ‘what a mind is.’ There is much to gain in understanding how minds relate to the rest of reality, and the first steps to inquiring in this way are to understand that the mind is a concept, that reality is a concept, and it is primarily in this way that they can interact. Rather than the mind’s being of a particular substance being a fact objectively, it is one determined by a subject. Thinking in that way allows for a pluralistic attitude towards what minds are, enriching our concepts not only of minds but everything else as well.

This is an essay I wrote for a class on the Philosophy of Mind. It is my first philosophical essay I am not counting Mr. Kaninchente. and it outlines some aspects of my approach. To be honest, this essay is not organized well. I use a lot of terms before explaining what they mean, if I explain at all.

I structured the essay around questions. I begin with the question of “how are we able to talk about books without having a good definition of one?” From there, I seek answers. I find more questions, seek more answers, more questions, more answers, and so on. My expectation when writing this was that the reader would take time to contemplate the questions I raise, coming up with assent or objections. “This would orient them to the direction I am headed, so that we would take this journey of exploration together.”

If you find this essay interesting, or if you cannot make heads-or-tails of it, please stick around—I will write more about these concepts in more detail and with greater accessibility. Consider subscribing so that you get notified when I publish those!

Back to the essay…

I know what a book is. Precisely? No, probably not, but I can tell you if something is a book or not. Well, if you hand me a long scroll with the contents of a short book, I might have a hard time deciding whether it is one or not. I know of a few ways in which it is like a book, and a few ways it isn’t. I am able to tell you these things because books are meaningful to me; I just about know what you mean when you talk to me about books. We can generally agree on what are and aren’t books, how we interact with them, and how they interact with us. But how are we able to talk about books without having a good definition of one? After all, books come in many different colors and sizes, different languages and sometimes none at all, and they can even be digital. As a result of the fact that I cannot really tell you what makes something a book by identifying the necessary and sufficient properties of books, it should be something else, not something intrinsic to the thing itself, that gives me knowledge of books. What is that something else?

Rather than receiving that knowledge, I constructed it. When I learned the word ‘book,’ I looked at such ‘books’ and recognized them as such. The alphabet book, the bedtime storybook, etc. Reflectively, it seems like this meaning of what a book is derives from my associating of things as books. As a subject begins to associate composites of particulars of their experience with each other, those composites become abstracted as particulars of experience themselves, and, as a result, concepts are formed. To remove any implication on anything ‘out there’, experience here is completely phenomenal. It includes illusion and hallucination. A ‘particular of experience’ is anything experienced as meaningfully distinct, as I can distinguish the books on my bookshelf from each other. But what is ‘meaning’? I can get meaning from a sentence, so that I can read books and understand them. While driving, if I see an octagonal red sign, I will come to a stop; the sign is meaningful. Meaning is, for a subject, the effect anything has on that subject’s actions and experiences, for instance how books are meaningful to me as things to read. Now, what is a concept? Looking at the things I call concepts, like ‘book’ and ‘car,’ they are ways I divide up the world. A concept is an abstraction of particulars of experience, as I recognize each distinct book on my bookshelf as a ‘book’. Ok, so what about composites of those particulars? Composites of particulars are nothing more than the individual particulars, until they are associated and form meaning as a whole. It is in this way that my edition of Non-physical theories of consciousness Mørch, Hedda Hassel. Non-Physicalist Theories of Consciousness. Cambridge University press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009317344. A class textbook. has meaning, and it is in this way that my concept of ‘book,’ in general, has meaning.

But if all it takes to be a book is for me to arbitrarily decide so, what do I make of things of which I have not yet made an arbitration? Surely it isn’t completely arbitrary! Experience says otherwise—I can tell you some general characteristics of a book: some assortment of text combined sequentially. It is in my recognition of this that I am able to reason through the book-ness of things. The associations a subject makes between composites of particulars of experience are actually associations of isomorphisms, a term for when the particulars of the composite can themselves be associated Hofstadter, Douglas R. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Basic Books, 1979. Pages 49-50 were a major source of inspiration, thought partially a misreading.. A long scroll can connect in meaning to a book through some of its similar structure: it is made of paper, it can be held, it can be read, etc. The concepts ‘made-of-paper,’ ‘holdable,’ and ‘readable’ are recognized between the two.

So then, what is a mind? Just like a book is meaningful as a book in terms of the concept of ‘book,’ a mind is meaningful as a mind in terms of the concept of ‘mind.’ A specific book title may jump out at me, and that specific title is not part of my concept of book, so a book can be meaningful in ways other than its meaning as a book, like in relation to other concepts, or in pre-conceptual association with isomorphisms. The same is true of minds; though it may be more difficult to experience particulars of minds. Great, but what is the point? The point is realizing that minds are not primarily things external to us, but that minds are primarily things internal, and only secondarily external. The point is being able to examine the various theories of what minds are, and realizing what is really going on when one theory sounds unappealing. Is it really that it seems false, or does it use a concept of mind with meanings inconsistent with yours? … Oh, you really think that it isn’t true, huh. Then I ask you, what is truth? What does it mean for something to be the case?

In everyday life we talk about things being the case all the time: “rest days are great,” “there is class,” “I am late.” In each of these cases there is an appeal to being: ‘are,’ ‘is,’ ‘am.’ That is no problem for getting around, but in philosophy, that poses quite a metaphysical problem! How can we know about reality without knowing what reality is Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Edited by Dennis J. Schmidt, Translated by Joan Stambaugh, State University of New York Press, 2010. The first introduction, especially its first pages, outline the importance of the question.? Hold on—there are two problems here. For one, we do seem to know about reality, evident in that we have ‘no problem getting around.’ For another, it seems that what we would want to look for is something about what reality is, what being is, what is is. Evidently, we won’t be able to define the being of being, as any attempt to define being would rely on a definition of being Heidegger outlines this point in his first introduction, pointing out that this unique problem means thinking about Being is even more important..

Those two problems can be resolved by realizing that reality, or being, is also a concept. I am, my books are, this paper is. A subject abstracts the concept of being from the particulars which are meaningful as being. But then, when I am talking about a book, am I really talking about something that exists? That is real? Well, yes, since what it means for something to exist and be real depends on your own conception of existence and reality. “No, I mean ‘out there.’ Does the book exist objectively?” Well, if ‘out there’ includes somebody else’s conception of the book, then maybe it does. Even if nobody is around to have concepts of the book, maybe it exists, who’s to say? It seems like that book may indeed exist outside my concept of it, and maybe not.

But isn’t that book something that I made up, through my own associations of isomorphisms, into my own concepts? I’ve already said that it isn’t that book that makes it that book, so how can that book be that book in itself? Anything I think might exist objectively is intrinsically subjective. And I am still thinking that things can be, but have already seen how being is a concept, and thus created as well. It is definitely influenced by the way other people use the terms I associate with the concept ‘being,’ but then it is socially created rather than personally created. Great, but what is the point? The point this time is to realize what it means to agree and disagree with different philosophical views. It isn’t so much that I like the representational theory of mind, which is physicalist, because I think it is more ‘real,’ but because they nest better in my web of concepts. I am able to see the many ways in which thinking of the mind like that has benefits, such as in understanding how meaning can possibly connect to a mechanical world. But I am also able to see the ways in which dualism, which makes the mind mental, can help me think about the ‘concepts’ and ‘thoughts’ and ‘experiences’ as mental states that I have, all without referring to the syntactic manipulation of other theories, as is the case in the representational theory.

Why limit my experience and understanding of mind by some made-up concept of truth and reality? Thinking that a theory is false outright is different from understanding how a theory is incompatible with other immanent understanding, like understanding how exactly Searle’s Chinese Room refutes the representational theory of mind. I’ll introduce nuance into my conceptual map by de-emphasizing my concept of truth, and prioritizing the pragmatic merit of a plurality of perspectives. Holding this plurality of perspectives, even if they are contrary to each other, can (and has, in my experience) enable bigger and greater interaction with other concepts and pre-concept meaning: there is a greater pool of isomorphisms to associate. Even those theories which outright deny the mind, like the identity theory which states that the mind is equivalent to the brain, may be fruitful to hold, while simultaneously holding idealist theories in which everything is mental. The value of truth is that it is objective and eternal. Upon realizing that it is subjective and circumstantial, as I have argued, all we are left with is pragmatism.

“Hold on, how can two contradicting views be held simultaneously?” That seems impossible, or at least irrational. But contradicting views are often held—for example, classical mechanics describes a world of physics in a way that does not work on the quantum scale, and quantum theories don’t work on the classical scale. Physicists clearly understand and utilize them. Having both theories in mind is useful not only in helping describe the world meaningfully, but also in enabling interactions between the theories and the other concepts held; increasing the explanatory power of the conceptual map. Clearly, this isn’t irrational, but the criticism stands that these two theories aren’t really being “held simultaneously:” one is used when the other fails. Now consider an example—If you think there is a 60% chance of rain tomorrow, you simultaneously think, in a sense, that it is going to rain tomorrow and you think that it isn’t going to rain tomorrow. This nuanced view embraces what appears to be a contradiction, but it really isn’t a contradiction because neither conjunct is taken as ‘completely true.’ A contradiction has to involve incompatible statements of truth. For example, holding it to be completely true that it will rain tomorrow, and that it will not rain tomorrow. Or, when the credences are incompatible, such as thinking that there is a 60% chance of rain, and a 60% chance of not-rain. Remember, however, that truth is made up—it is a concept that hides what is really going on in concept-meaning interactions. Without any appeal to some objective truth, there is no contradiction.

Another criticism concerns the issue of arguing against the reality of mind through the use of ‘meaning’ and ‘concept.’ The problem with this criticism is that for it to hold, ‘meaning’ and ‘concept’ need to be real, while the mind unreal. However, ‘meaning’ and ‘concept’ are themselves concepts, which aren’t necessarily real. In any case, what it means to be real isn’t clear at all. The arguments I make needn’t be ‘true’ or match up with ‘reality,’ but be meaningful to those who understand them. This meaning interacts with the other meaning people have, enriching the reality that a person creates. The point is not primarily to be correct, but primarily to make an impact, so that people can question and figure out what being ‘correct’ means.

‘Mind’ is a concept, which is meaning. As meaning, it is able to interact with whatever it means to philosophize about the mind. ‘Reality’ is also a concept, and as such is able to interact with the other concepts we have. A rich network of meaning becomes richer with more interpretations of ‘mind,’ and adopting such interpretations is possible once realizing that ‘truth’ is limiting. The mind is physical, mental, both, and neither—not because those are ‘true,’ but because they are meaningful together.

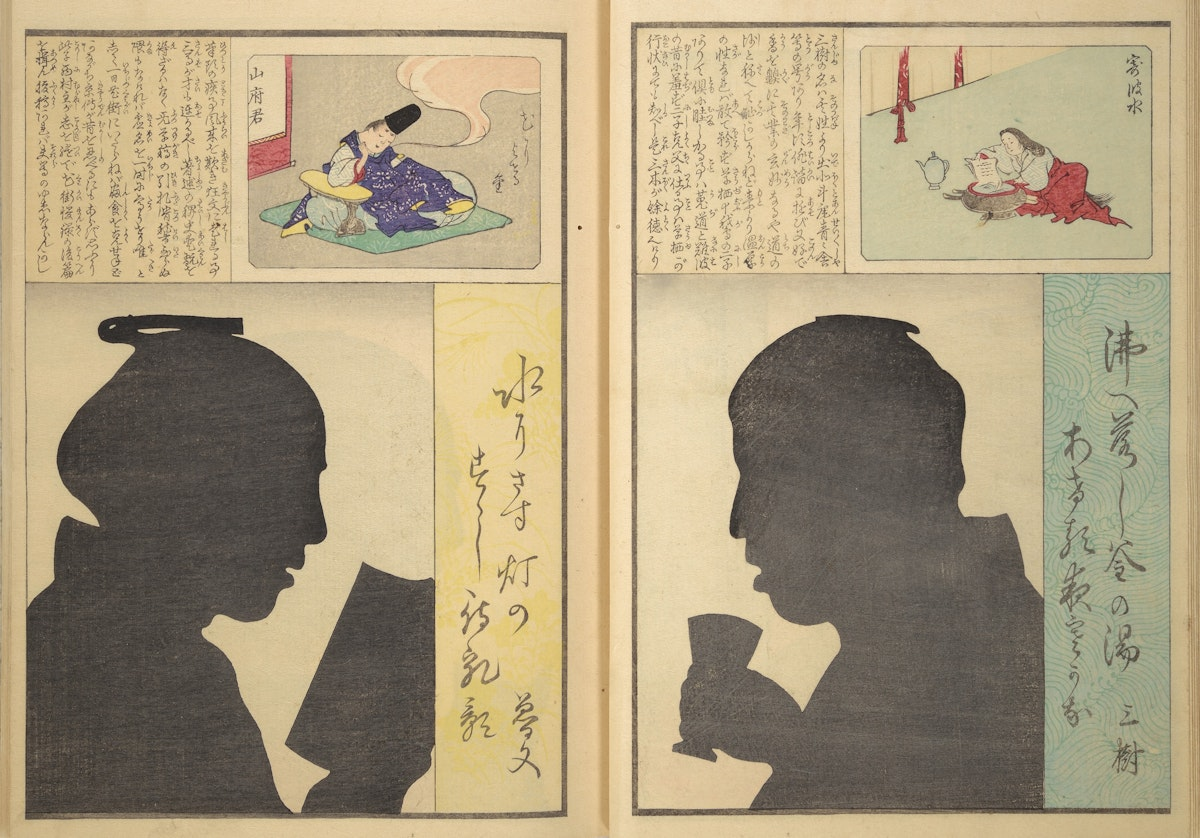

Images from Clear Shadows (1867).